Martin Wiesner

Anhalt University of Applied Sciences

Anhalt, Germany

The design discipline offers an almost all-encompassing care of human needs. In some cases, even needs that people themselves are hardly aware of. For the purpose of a well-being orientation perception-centered design of all things and information with which we interact as humans it would be important to achieve design literacy.

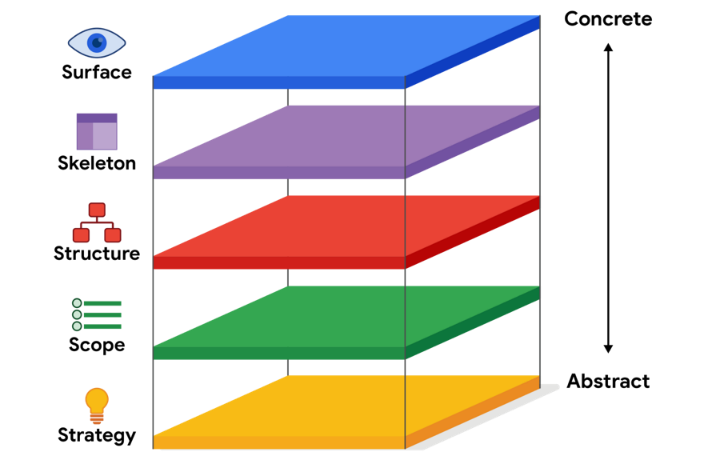

To clarify what is meant by this, it is worth looking at the levels of design according to Garrett (2002), which are arranged in different stages from very concrete at the top to abstract at the bottom. All these levels are of course of great importance and familiar to designers. From our point of view, it would be of unimaginable value for well-being and avoidance of visual noise and confusion if larger parts of the society would develop design literacy in these areas.

The lower two levels (strategy and scope) can lead to increased well-being through appropriate human-centered conception and user-research. The upper three levels (surface, skeleton and structure) can lead to perceptually appropriate content or products that are easier to understand, clearly structured and aesthetically pleasing, give indications of the type of interaction, correctly prioritize elements according to importance and enable a personal relationship to the content. The focus of this contribution will be the perception-centered design, which should be taught as literacy to provide better experiences in daily life. The focus is therefore chosen because it seems rather underrepresented. The focus on wellbeing seems to be more in the public eye and the relative breadth of coverage of design thinking seminars seems to suggest that something is happening here, at least to some extent. It can also be concluded from practical observations in teaching in an interdisciplinary Master’s programme that teaching design on the basis of perceptual needs can be argued very well and is well suited for people who are less artistically inclined. But what does perception-centered mean? A first central insight can be to derive requirements for design from individual, definable levels of perception. In the following, the levels of the perception model by Leder et al. (2004) will be consulted:

- The first level is the organisation of perception. The brain tries to find a coherent perception from the sensory information. Some object properties (such as symmetry) make this organisation more fluid, i.e. easier. The principle of “unity-in-diversity” according to Post et al. (2013) states that product designs that maintain unity in as much diversity as is justifiable are the most aesthetically pleasing.

- The next stage is implicit memory integration. Here, an identification process takes place based on known and typical features. Similar to the first level, an adequate level between safety needs, in this case typicality, and needs for fascinating, aesthetic content, in this case novelty, must be found in order to correspond to an aesthetic preference according to (Hekkert und Blijlevens 2014).

- At the transition between subconscious and conscious perception, the third stage, within the implicit system, is to decide whether the perceptual content is remarkable enough to be processed consciously. A certain disfluency increases the chance and generates conscious attention.

- Within the explicit classification, the already implicitly preprocessed contents are now consciously classified into mental categories to be able to interpret them. Here, it should be possible to classify the elements through existing experiences, otherwise this tends to lead to negative experiences.

- The final phase of perception comprises the processes aimed at grasping the meaning of the design object. If an existing disfluency can be resolved, an “aesthetic AHA” can result, which represents the joy of gaining knowledge and leads to a reward effect (Graf und Landwehr 2015). At the semantic level, hypotheses arise about existing Affordances and references to the self-concept that can ideally be resolved positively.

From the levels of perception, it can be extracted the following things should be achieved through perception-centered thinking:

- Balance of unity and diversity

- Balance of familiarity and novelty

- Recognizable classification and regularity of a design principle and at the same time the ability to fascinate for important elements of the design.

- Prominent affordances and comprehensibility of possible interactions with them.

- Balance between suitability for self-expression and social conformity.

- Responsibility to carefully consider which elements need to attract attention.

To achieve all this, it is important to recognize that designing is largely about creating order. It must be consciously weighed up where and with what aim this order should be deviated from. Design literacy would be desirable for this ability to provide better experiences for all.

References

Chaurasia, Aanchal (2021): What I learnt from Google’s “Foundations of UX design” course. Online verfügbar unter https://bootcamp.uxdesign.cc/what-i-learnt-from-googles-foundations-of-ux-design-course-d2c953d79ebe, zuletzt aktualisiert am 13.05.2021, zuletzt geprüft am 02.10.2022

Garrett, Jesse James (2002): The elements of user experience. User-centered design for the Web and beyond. 2nd ed. Berkeley, CA: New Riders.

Graf, Laura K. M.; Landwehr, Jan R. (2015): A dual-process perspective on fluency-based aesthetics: the pleasure-interest model of aesthetic liking. In: Personality and social psychology review : an official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc 19 (4), S. 395–410. DOI: 10.1177/1088868315574978.

Hekkert; Blijlevens (2014): Influence of Social Connectedness and Autonomy on Aesthetic Pleasure for Product Designs.

Post, R. A. G.; Blijlevens, J.; Hekkert, P. (2013): The influence of unity-in-variety on aesthetic appreciation of car interiors.

Martin Wiesner is a designer in research transfer at the Anhalt University of Applied Sciences and a freelance designer.

He supports research projects in developing their full effectiveness through design services.

In his doctoral thesis he is working on design preference acquisition and product design optimisation.

His research interests are sustainable design, 3D design, methods and tools of product development and research transfer.

back to the Symposium Programme