Eva Lutnæs

Oslo Metropolitan University

Oslo, Norway

This paper will explore how critical design literacy is demonstrated by non-designers challenged to claim a role as redirective design practitioners (Fry, 2007; Manzini, 2009). The non-designers in the study are Norwegian pupils in a lower secondary school age 15-16 and critical design literacy are located in the pupils’ submissions for an ecovillage project. A key premise underlying the research in this paper is a shift from design as a practice of shaping consumerist culture and creating desire for new products (Mateus-Berr et. al., 2013). Design is regarded as a practice of empathy, criticism, and responsible transformation. Responsible transformations derive from connecting to real-world dilemmas with empathy, rejecting destructive products of human creativity and focusing on problems that are worth solving (Lutnæs, 2020). In lower secondary school, the teachers make the project briefs and choose what challenges of the real-world to bring into the design studios and to the pupils’ attention. In this case, the concerns to battle were social isolation and the carbon footprint of housing.

Since my very first year as a lower secondary teacher (school year 2015/2016), I have had the privilege of collaborating with local housing developers to design an architectural competition for the level 10 pupils (age 15-16). The project briefs for the competitions were always based on a case the housing developer was facing at the time and designed according to the competence goals in the current national curricula. The project briefs are mediating artefacts that transform the studio into a learning space (Orr & Shreeve, 2018) and indicate what kind of design responses that would be evaluated as valuable. In 2020/2021, a local housing developer initiated an architectural competition that challenged pupils to design shared-living spaces for a planned ecovillage. Their vision for the shared-living spaces was to enable mixed-use, inclusive social interaction, and to lower the overall carbon footprint of the 50-60 inhabitants in the ecovillage.

The project brief is open-ended and left for the pupils to decide which features they wanted to offer in the shared-living spaces as a response to the visions from the local housing developer. Addressing the task of shared-living spaces, the pupils engaged with the socio-ecological consequences of their proposed solutions and confronted value conflicts and dilemmas such as: “What are people capable of sharing?”, “Should the shared-living spaces be accessible for the public or exclusively for the ecovillage community?”, “What is the socio-environmental impact of shared sports facilities, compared to shared facilities for farming and processing of food?”. Challenging questions emerged in the studio as pupils navigated conflicting interests and ethical concerns towards their final shared-living spaces concept. Their submission in the project is a digital presentation with pictures and critical review of their proposed solutions with concerns to environmental protection and human well-being. The Ecovillage project enables pupils to gain first-hand experiences with design as a redirective practice, and to discern the possibilities of architecture to nudge change in our modes of being in this world as societies and as individuals. How do pupils respond to the challenge of exploring and voicing the more responsible alternatives? What design literacies might be located in their submissions?

In earlier articles, I have reviewed the competence goals of the new Norwegian national curriculum in the subject Art and Crafts for primary and lower secondary education (Lutnæs, 2020) and the design of two projects for lower secondary school from a teacher’s perspective (Lutnæs, 2021) through a framework consisting of four narratives on how to cultivate critical design literacy (Lutnæs, 2019;2021).

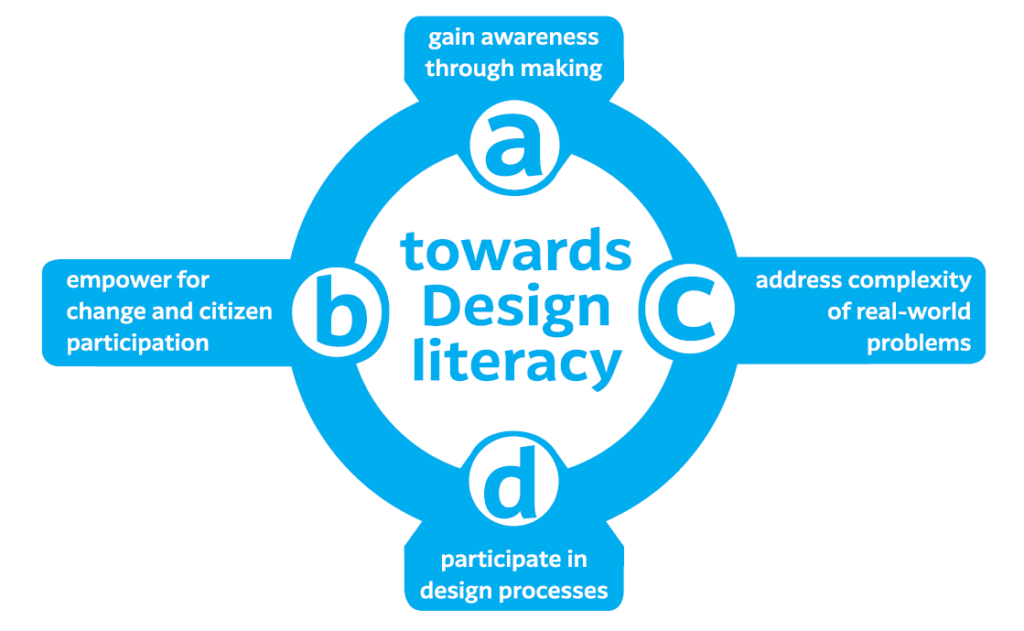

Figure 1. Model of the four narratives in Lutnæs (2020).

The four narratives provide a tool to plan and evaluate projects, educational resources, and a critical lens to review visions, discourse, and educational programs. They are however insufficient means when it comes to a study of pupils’ submissions. The narratives are tools to support the pupils in their learning of critical design literacy, the submissions are the final results of a design and learning process. In order to approach how design literacy are demonstrated in the pupils’ submissions I will rely on the definition of what it means to be a design literate derived from the four narratives:

Being design literate in the context of critical innovation means to be aware of both the positive and negative impacts of design on people and the planet, approaching real-world problems as complex, voicing change through design processes, and judging the viability of any design ideas in terms of how they support a transition towards more sustainable ways of living (Lutnæs, 2019, p. 1303; Lutnæs, 2021, p. 10).

The empirical material consists of 32 submissions and the definition above turns the lens to what changes the pupils voice, what kind of features they suggest for the shared-living facilities in the ecovillage and to the words the pupils use to explain and justify their concept. I move between different modes of practices as I work both as a teacher in lower secondary education and as a professor at the university. In this study, the role as a teacher serves as a ‘mediating component’ (Dunin-Woyseth & Nilsson, 2012, p. 3) between the field of academia and the field of general education to advance our understanding of how pupils might demonstrate critical design literacy.

References

Dunin-Woyseth, H., & Nilsson, F. (2014). Design Education, Practice, and Research; on building a field of inquiry. Studies in Material Thinking, 11, 1–17.

Fry, T. (2007). Redirective Practice: An Elaboration. Design Philosophy Papers, 5(1), 5–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/144871307X13966292017072

Lutnæs, E. (2019). Framing the concept design literacy for a general public. Conference Proceedings of the Academy for Design Innovation Management, 2(1), 1295–1305.

Lutnæs, E. (2020). Empowering Responsible Design Literacy: Identifying Narratives in a New Curriculum. RChD: creación y pensamiento, 5(8), 11-22. doi:10.5354/0719-837X.2020.56120

Lutnæs, E. ., Nielsen, L. M. ., & Digranes , I. (2021). Editorial. Norwegian papers from the Academy for Design Innovation Management Conference – ADIM 2019. FormAkademisk , 14(4). https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.4708

Manzini, E. (2009). Viewpoint: New Design Knowledge. Design Studies, 30(1), 4–12 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2008.10.001

Mateus-Berr, R., Boukhari, N., Burger, F., Finckenstein, A., Gesell, T., Gomez, M., … Verocai, J. (2013). Social design. In J.B. Reitan, P. Lloyd, E. Bohemia, L.M. Nielsen, I. Digranes & E. Lutnæs (Eds.), Design Learning for Tomorrow. Design Education from Kindergarten to PhD. Proceedings from the 2nd International Conference for Design Education Researchers, vol. 1. (pp. 431–441). Oslo, Norway: ABM-media.

Orr, S., & Shreeve, A. (2018). Art and Design Pedagogy in Higher Education: Knowledge, Values and Ambiguity in the creative Curriculum. Routledge.

Eva Lutnæs is a professor in art and design education at Oslo Metropolitan University. She is head of the research group Design Literacy that focus on the role of design education in promoting responsible citizenship towards more sustainable societies. As an internationally awarded academic she has demonstrated the expertise of making research relevant across educational levels on topics such as assessment, responsible creativity, design literacy and education for sustainable development.

back to the Symposium Programme